Morocco’s Interior Ministry said Saturday morning that at least 632 people had died, mostly in Marrakech and five provinces near the quake’s epicentre, The Associated Press reported. Another 329 people were injured. Casualties are expected to rise as search for the missing continues and rescuers make it to remote areas in the Atlas mountains.

World leaders have extended their condolences and offers for help for the north African nation, even as aftershocks continued to reverberate, keeping people on their toes. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in a tweet Saturday morning, offered “all possible assistance” to Morocco.

Shallow and dangerous

As per the US Geological Survey, the earthquake, which hit at 11.11 pm local time (3.41 am IST), had a magnitude of 6.8. An aftershock of magnitude 4.9 earthquake rocked the region just 19 minutes later.

The epicentre of the quake was the town of Ighil, roughly 70 km south west of Marrakech. The USGS reported that the epicentre was roughly 18.5 km below the Earth’s surface, though Morocco’s own seismic agency pegged the depth at 11 km. Either way, it was a fairly shallow quake.

According to experts, such quakes are generally more dangerous as they carry more energy than when they emerge to the surface, when compared to quakes that occur deeper underneath the surface. While deeper quakes do indeed spread farther as seismic waves move radially upwards to the surface, they lose energy while travelling greater distances.

A rare quake and no preparation

Earthquakes are also not very common in North Africa, with seismicity rates comparatively low along the northern margin of the African continent, according to the USGS. Lahcen Mhanni, Head of the Seismic Monitoring and Warning Department at the National Institute of Geophysics, told 2M TV that the earthquake was the strongest ever recorded in the mountain region, The AP reported.

This means that unlike regions which frequently face such quakes, Morocco was also not prepared for such a calamity. While a 1960 earthquake, which killed thousands, did bring about changes to construction rules, most Moroccan buildings, especially in rural areas and older cities, are not built to withstand such strong tremors.

In Marrakech, many houses in the tightly packed old city, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, had collapsed. Footage of the mediaeval city wall showed big cracks and sections that had simply fallen off. Rescue teams are currently working to find people underneath the rubble. Many people continue to stay outdoors in fear of another quake.

In villages near the epicentre, things were possibly even worse. “Our neighbours are under the rubble and people are working hard to rescue them using available means in the village,” Montasir Itri, a resident of the mountain village of Asni near the epicentre, told Reuters, adding that most of the houses in the village were damaged. Villages such as Asni lie on the Atlas mountains, making access a major issue for authorities and rescue teams.

Why the quake occurred

While seismicity rates are indeed lower in the region, making earthquakes rarer, they are not completely unheard of. According to the USGS, “large destructive earthquakes have been recorded and reported from Morocco in the western Mediterranean”.

Such quakes occur due to the “northward convergence of the African plate with respect to the Eurasian plate along a complex plate boundary.” With respect to yesterday’s quake, the USGS attributed it to “oblique-reverse faulting at shallow depth within the Moroccan High Atlas Mountain range”.

A fault is a fracture or zone of fractures between two blocks of rock. Faults allow the blocks to move relative to each other, causing earthquakes if the movement occurs rapidly. During a quake, the rock on one side of the fault suddenly slips with respect to the other.’

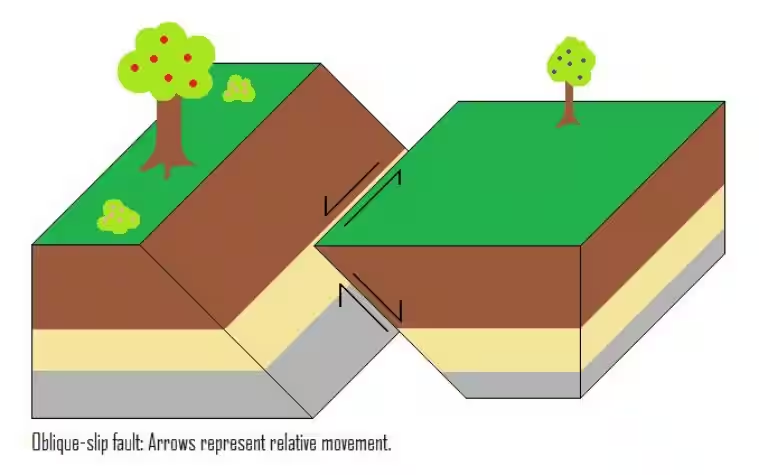

Scientists use the angle of the fault with respect to the surface (known as the dip) and the direction of the slip along the fault to classify faults. Faults which move along the direction of the dip plane are dip-slip faults, whereas faults which move horizontally are known as strike-slip faults.

Oblique-slip faults show characteristics of both dip-slip and strike-slip faults. The term ‘reverse’ refers to a situation that the upper block, above the fault plane, moves up and over the lower block. This type of faulting is common in areas of compression — when one tectonic plate is converging into another.

This report is generated from Indian Express news service. The Sen Times holds no responsibility for its content.