Adelaide, May 26 (The Conversation) You’ve probably heard the terms “abs” and “core” used in social media videos, Pilates classes, or even by physiotherapists.

Given they seem to refer to the same general area of your body, you might have wondered what the difference is.

When people talk about “abs”, they’re often referring to the abdominal muscles you can see. Conversely, the term “core” is used to describe a broader group of muscles in the context of function, rather than aesthetics.

While abs and core are often spoken about separately, there’s a lot of overlap between them.

What are abs?

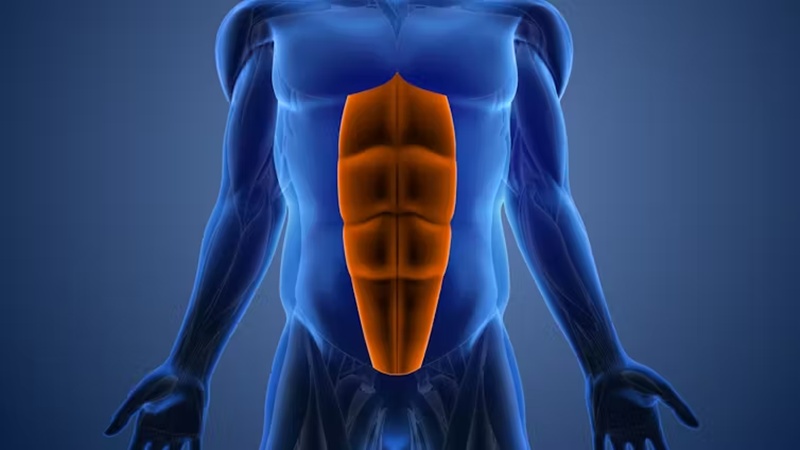

The term “abs” is short for abdominal muscles. These are the muscles that run along the front and side of your stomach.

When someone talks about getting a six-pack, they’re usually referring to toning the rectus abdominis, the long muscle that goes from the bottom of your ribs to the top of your pelvis.

Your abdominals also include your obliques, which sit on the side of your body, and your transverse abdominis, which sits underneath your other abdominal muscles and wraps around your waist like a belt.

The term “abs” has been around for a long time, and is perhaps most often used when discussing aesthetics.

For example, it’s common to see health and wellness publications offering advice on how to achieve “flat” or “six-pack” abs.

What about the core?

When people talk about the “core”, they are often referring to your abdominals, but also the muscles in your back (your spinal erectors), hips, glutes, pelvic floor, and your diaphragm.

These are the muscles that can stabilise your spine against movement, and aid in the transfer of force between the upper and lower limbs.

The term “core” wasn’t commonly used until the early 2000s, when it became synonymous with core training.

While the exact reason for its surge in popularity isn’t clear, it most likely followed a study published in 1998 that suggested people with lower back pain might have impaired function of their deep abdominal muscles.

From there, the concept of “core training” entered the mainstream, where it was proposed to reduce lower back pain and improve athletic performance.

What does the evidence say?

When we consider all the muscles that make up the core, it seems obvious they would be important – but it might not be for the reasons you think.

For example, having good core stability doesn’t necessarily prevent lower back pain, as it’s been touted to do.

There’s evidence suggesting core stability training, which might include exercises such as planks and dead bugs, can help reduce bouts of lower back pain. However it doesn’t appear to be any more effective than other types of exercise, such as walking or weight training.

Other research suggests there aren’t any differences in how people with and without lower back pain recruit and use their core muscles.

In a separate study, improvements in core strength and stability after a nine-week core stability training program were not significantly associated with improvements in pain and function, further questioning this relationship.

The link between core strength and athletic performance is also unclear.

A 2016 review found some very small associations between measures of core muscle strength and measures of whole body strength, power and balance. However, because of the design of the studies reviewed, we don’t know whether people who have better strength, power and balance simply have stronger core muscles, or whether stronger core muscles increase strength, power and balance.

An earlier review summarised the effect of core stability training on measures of athletic performance, including jumping, sprinting and throwing. It concluded this type of training is unlikely to provide substantial benefits to measures of general athletic performance such as jumping and sprinting.

However, this review also suggested that, given the important role of the abs in torso rotation, strengthening these muscles might have merit in improving performance in sports that involve swinging a bat or throwing a ball.

This is likely to apply to other sports that involve rapid torso movement as well, such as mixed martial arts and kayaking.

How can you exercise your abs and core?

There’s good evidence that simply getting stronger by lifting weights can help prevent injuries. Training your core to get stronger should have a similar impact, as long as it’s part of a broader training program.

We also know having weaker muscles makes you more likely to experience functional limitations and disability in older age. So alongside any other potential benefits, improving core strength with the rest of your body could help keep you fit and healthy as you get older.

There are plenty of exercises you can do to train your core and abs.

If you’re new to core training, you might want to start off with some lower-level isolation exercises that don’t involve any movement of the core. These include things like planks, bird dogs, and pallof presses. These are unlikely to cause too much muscle soreness, but will train your core muscles.

Once you feel like these are going well, you can start moving into some more dynamic exercises such as sit ups, Russian twists and leg raises, where you train your abdominals using a full range of motion.