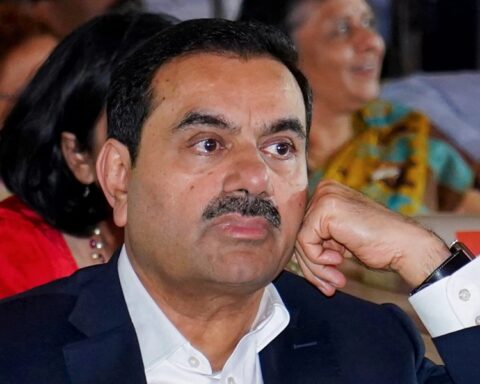

NEW DELHI, Nov 28 (Reuters) – Bribery allegations against Adani Group founder Gautam Adani have highlighted the growing problem India’s renewable energy developers face in finding buyers for the power they generate.

While India’s central government wants to shift away from polluting coal-fired generation towards solar and wind, officials say state government-owned power distribution companies responsible for keeping the lights on have dragged their heels over striking renewable purchase deals.

U.S. authorities allege that Indian billionaire Adani conspired to devise a $265 million scheme to bribe Indian state government officials to secure solar power supply deals, after one of his companies was unable to secure buyers for a $6 billion project for several years.

The Adani Group has denied the charges.

The conglomerate is not alone in facing increasingly long delays in signing up buyers for the renewable electricity capacity which is now being developed in coal-dependent India – the world’s third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Coal accounted for 75% of India’s power generation during the year to the end of March, with renewables such as solar and wind, but not including hydro-electricity, making up about 12%.

India is still more than 10% short of its much-publicised pledge to add 175 gigawatts (GW) of renewable power by 2022.

That has led the federal government to ramp up bidding for renewable projects to meet an ambitious 2030 target of increasing its non-fossil fuel capacity to 500 gigawatts (GW).

In the five years to March 2028 it plans to tender for more than four-times the capacity of renewable energy projects it commissioned in the preceding five.

To push states to help meet India’s overall goal, New Delhi in 2022 introduced so-called renewable purchase obligations (RPOs), which mandate that states increase clean energy adoption so that the national share doubles to 43.3% in March 2030.

Honouring these RPOs would require 20 of the 30 provinces monitored to more than double the share of green power in their electricity mix, a February report by government think-tank NITI Aayog showed.

The problem is that India’s states are unprepared for the rapid rise in renewable generating capacity, lack adequate transmission infrastructure and storage and would rather rely on fossil fuel for supply than risk “intermittent” renewables.

The challenges were stark in the case of Adani Green, India’s largest renewable energy company, which took nearly 3-1/2 years to strike supply deals with buyers for the entire 8 gigawatts (GW) of solar power capacity it won in a tender widely publicised as the country’s biggest.

DEMAND POOL

Yet setting targets for tenders and issuing contracts is “meaningless” so long as interest from power distribution companies is so low, said R. Srikanth, energy industry adviser and dean at India’s National Institute of Advanced Studies.

And the allegations against Adani are likely to result in a further renewables slowdown, as low-cost finance from foreign investors may become more difficult to secure, Srikanth said.

A change in the way some tenders are run has exacerbated delays in the time it takes to complete renewables projects.

The tender won by Adani Green was the first major contract issued by state-run Solar Energy Corp of India (SECI) without a state-guaranteed Power Purchase Agreement (PPA).

When announced in June 2019, SECI said buyers were guaranteed, but it withdrew the provision from the deal signed a year later.

SECI’s chairman told Reuters last month that a three-fold increase in tendering of renewable projects has left 30 GW of projects for which bidding is complete, but without buyers.

“You can’t expect the states to respond and start signing three times the power supply agreements,” R P Gupta told Reuters in an interview, adding that a “demand pool has to be created” and states had to be “sensitised” to renewables.

Brokerage JM Financial said that it now takes 8 to 10 months to sign power supply deals after a contract is awarded.

By comparison, companies that were awarded contracts between July 2018 and December 2020 needed around three months to strike supply deals, SECI data showed.

“The sudden surge in bids, large pipeline of projects under construction, mismatch in power demand and bid-pipeline … and constraints in timely execution of projects are leading to delays in signing,” JM Financial said.

Renewable energy projects have also seen cancellations, with about 4%-5% of all tendered projects annulled, and backlogs in transmission infrastructure development, Gupta said.

One solution, said Rakesh Nath, former chairman of India’s Central Electricity Authority, would be knowing how much power buyers want before projects are bid for.

“Taking buyers into confidence before inviting bids may minimise delays in signing power supply agreements,” he said.